- Date

- 17/10/1994

- First

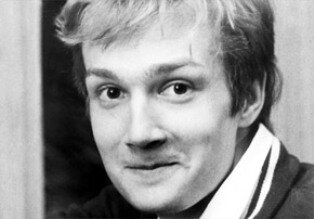

- Dmitry

- Surname

- KHOLODOV

- Sex/Age

- M, 27

- Incident

- homicide

- Motive

- J

- Place

- office

- Job

- journalist

- Medium

- Federal District Plus

- Moscow

- Street, Town, Region

- 1905 St, Moscow

- Freelance

- no

- Local/National

- national, Moskovsky komsomolets

- Other Ties

- Cause of Death

- murder, explosives

- Legal Qualification

- 103 (murder; 1960 Criminal Code)

- Impunity

- trial, acquittal, 26 June 2002 & 10 June 2004

[Update, June 2010]

On 21 June 2010 Dmitry Kholodov would have celebrated his 43rd birthday. He was murdered, at the age of 27, on 17 October 1994. “He was not killed in a war, he died for the truth.” These words are engraved on the memorial plaque at the Moskovsky komsomolets editorial offices. For many people in the power ministries Dmitry was a very awkward journalist. He worked in many hot spots around the former Soviet Union and told the whole truth about war. It was the dream of many high-ranking officers and officials “to shut him up”.

The deadline for completion of the preliminary investigation into his murder has been extended numerous times. The last deadline was 14 August 2008. Then the investigation was halted (but not closed) on the grounds laid down by point 1, part 1 of Article 208 (Criminal Procedural Code), “failure to identify the responsible persons”. When his newspaper formally applied to the RF Prosecutor General’s Office for an update on the state of the investigation it was told, “At present law-enforcement agencies continue their investigations, aimed at establishing the persons who should be prosecuted” for Dima’s murder.

Based on report in “Dangerous Profession” weekly (21-27 June 2010), CJES

From “PARTIAL JUSTICE” report (June 2009)

On Monday morning, 17 October 1994, Dmitry Kholodov picked up a briefcase from the left luggage section at the Kazansky railway station in Moscow. Military correspondent for the Moskovsky komsomolets daily, Kholodov was due to speak at Duma hearings on corruption in the army in a few days time. A contact had offered him further materials to be left for collection in this way.

On returning to the newspaper offices Kholodov opened the case. It had been booby-trapped. The explosion killed him, injuring three others, in the same room and adjoining premises and causing wide damage.

BACKGROUND

Moskovsky komsomolets (MK) is a Soviet-era daily that retains wide popularity and a circulation of 1 million copies in Moscow and in numerous local editions across Russia. Its intended but by no means exclusive readership is young and it was then widely read in the armed forces.

Dmitry Kholodov grew up in the Moscow Region. After military service as a gunner with the marines, he studied at the Moscow Engineering Physics Institute, the main centre for training specialists in the atomic industry, and returned to work with his parents at the institute in Klimovsk. Opportunities in the defence industry were shrinking rapidly, however. Dima sought work as a journalist, first with local radio and then with Moskovsky komsomolets which he joined in 1992.

In 1993 he reported for the newspaper from Ingushetia, Chechnya, Azerbaijan, the Tajik-Afghan border and wrote a number of graphic articles about the conflict in Abkhazia, in which he criticised Russia’s role. At the end of that year Kholodov interviewed Pavel Grachev, the defence minister, concerning the violent clash which had just occurred in Moscow between supporters of President Yeltsin and the Supreme Soviet. This was the beginning of an animosity fuelled throughout the last year of Kholodov’s life by 18 more articles criticising the defence minister for one reason or another.

Kholodov wrote about conditions in the armed forces. He praised moves towards a professional rather than conscript army. A particular and sustained target of criticism was corruption in the Western Group of the armed forces. More than half a million soldiers, officers and their families had been withdrawn from the former East Germany in 1991 and, based on information from his sources inside the army and the ministry of defence, Kholodov detailed the misuse by high ranking officers and officials of the funds allocated to ease this transition. After a major article entitled “A military mafia exists in Russia” in which he linked Grachev to such abuses and scams Kholodov received threatening phone calls. For a while he disappeared, not even telling his newspaper where he had gone.

Soon, however, he resumed his investigations and privately told co-author Colonel Bykov and his MoD source Victor Baranets that he had discovered that professional assassins, from commercial and private companies, were being trained at the base of the 45th paratroop regiment.

INTERPRETATIONS

Following Kholodov’s murder the prime suspects were quickly identified, by at least two different sources. At their trial and afterwards they would claim that Prosecutor General Yury Skuratov had forced investigators to consider only their possible guilt when he informed President Yeltsin that Kholodov’s killers had been found. However, the evidence against them was strong and had been steadily accumulated.

Pavel Grachev did not hide his hostility towards Kholodov. When asked during an interview in April 1994 about the military threats and enemies that Russia faced the Minister of Defence told astonished TV presenter Vladimir Pozner that journalist Dmitry Kholodov was “the enemy within”. The fragment was not broadcast but made a considerable impression on the studio audience and was later retrieved and added to the case materials. MK’s military correspondent was already banned from news conferences at the Ministry and had been singled out for negative mention in reports to all military units. At the trial Grachev gave evidence as a witness and did not deny that he told subordinates to “sort out” Kholodov. If some had taken this to mean the journalist’s physical elimination, he added, that was a misunderstanding of his meaning and his words.

In the autumn of 1994 just before his death Kholodov had been working on four themes: Grachev’s various scams; corruption in the Western Group of the Russian armed forces; the situation in Chechnya; and what he was discovering about the Chuchkovo brigade (special unit) within the 45th paratroop regiment based in north-western Moscow.

To the public and fellow journalists there seemed little doubt why Kholodov had been murdered and who was behind the killing. Ten thousand filed past his coffin. His own newspaper openly blamed the Minister of Defence. By October 1994 the peacetime murders of eight others working in the media had already been recorded. This was the first time, however, that the motive was unmistakable and the manner of the killing, in broad daylight, was an unambiguous provocation. (The use of explosives against a journalist or media worker has only once been repeated in 2002 against Oleg Sedinko, the director of a Far Eastern TV company.)

INVESTIGATION

The Moscow prosecutor’s office opened an investigation under Article 102 (Murder; the 1960 Criminal Code was then still in force). Moskovsky komsomolets offered a reward of $2,000 for information leading to the identification of those involved in Kholodov’s murder. On 1 December 1994 a soldier with the 45th paratroop regiment rang the published MK contact number and met with a representative of the newspaper and the FSK officer assigned to take and investigate such calls.

Corporal Markelov identified officers from the special unit within his regiment (Majors Soroka and Morozov) as having made the explosive device and installed it in the briefcase collected by Kholodov. The next meeting with this source was cancelled when he and his regiment were sent to join the intervention in Chechnya. Over the next four months Markelov would only periodically return to Moscow from the North Caucasus. Meanwhile his identity, and the information he had passed on, was leaked by contacts in the FSK (predecessor of the FSB) and the organised crime squad to Colonel Popovskikh of the 45th regiment, who was later charged with having organised Kholodov’s murder. As a result, Markelov was put under pressure by his superior officers and encouraged to sign statements later used to discredit his evidence in court.

Only ten days after Kholodov was murdered, however, the organised crime department of the Moscow city police had received information from its own confidential sources. They also said that the 45th regiment were behind the killing and an unidentified informant recognised Morozov as the man directly responsible for the explosion.

From autumn 1995 to spring 1996 officers of the special unit at the 45th regiment were called in for questioning by the Prosecutor General's office. Pavel Grachev and two senior officers of the regiment were questioned but there was insufficient evidence, the prosecution believed, to hold them. Until autumn 1996 Grachev remained Minister of Defence and this presumably gave some protection to the suspects although electronic surveillance of their phones and apartments was being used to gather evidence against them. Early in 1998 six men were arrested and began to give evidence. Three including Popovskikh admitted their involvement in the assassination and gave details. In 2000 the case came to court.

TRIAL

The six men faced a range of charges from theft of ammunition, construction of an explosive device, the deliberate murder of Kholodov, the attempted murder of Yekaterina Deyeva and two others and deliberate destruction of property. Popovskikh was additionally charged with abuse of office. Since four of the accused were serving officers the case was heard before the Moscow District Military Court. For reasons of security the hearings took place not in the city centre courtroom but at the pre-trial detention centre where the accused were being held.

After two years Colonel Serdyukov and his fellow judges ruled that there was insufficient evidence to convict the accused. On 26 June 2002 they were all acquitted. Following the verdict the lead prosecutor Irina Aleshina gave a press conference at which she announced that the Prosecutor General's office would appeal against the decision and, for the first time, made public the physical threat and attempt at bribery she had faced as soon her appointment to the trial became known.

In Aleshina’s view there was “undeniable evidence” of the involvement of the accused. There was testimony by witnesses, confessions by several of the defendants, and the results of forensic and other expert tests. Though Popovskikh withdrew his previous testimony at the trial, his frank confession during the investigation had been given in the presence of his lawyer. The judge was also wrong, in Aleshina’s opinion, to discount Markelov’s evidence, partly on grounds that he had received a reward for his information.

The protest of the Prosecutor General's office was upheld by the military board of the Supreme Court on 27 May 2003 and two months later a new trial began. This was also held at the Moscow District Military Court but this time under Judge Yevgeny Zubov, who would subsequently preside at the Politkovskaya trial. The tone and manner of the proceedings were different but on 10 June 2004 the accused were again all acquitted. This time it was not just for lack of proof but for “lack of involvement”.

A second appeal was made to the military board of the Supreme Court. The prosecutors asked for the case to be sent to any other military court but that of the Moscow District. Kholodov’s parents also formally complained to the Supreme Court: Judges Serdyukov and Zubov had both falsified the daily records of the trial, they said, and the experts who investigated the type of explosive used were far from impartial. It was implied, for instance, that the charge had been much smaller than suggested and mainly intended to scare rather than kill Dmitry Kholodov.

APPEAL TO STRASBOURG

A year later the military board turned down the request for a re-trial. Having failed in their attempt to gain justice within the Russian judicial system the elderly parents of Dmitry Kholodov said they would now try to ensure that their son’s case received a fair hearing by appealing to the European Court of Human Rights in Strasbourg.

In August 2005 the complaint by Yury and Zoya Kholodov was accepted for consideration by the Court in Strasbourg. On 14 September 2005 the Court decided that Kholodov’s parents could not apply on his behalf since his murder took place before Russia was admitted to the Council of Europe (in 1996) and, more importantly, before it ratified the Convention on Human Rights. This was despite the advocacy of lawyers Karinna Moskalenko and Rachkovsky, who had successfully brought other cases to Strasbourg, and the urging of international bodies. This left a faint hope, perhaps, that the parents might apply on their own behalf. In 2005 they were already both 68 years old, however, and not in good health.